1940–1958 The Growth of Organized Research and Consolidation of the Parnassus Campus

1958: The Watershed Year for the San Francisco Campus

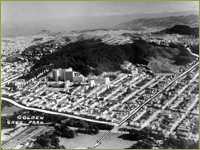

The San Francisco campus at mid-century was undergoing its most visible changes since the Affiliated Colleges had been built at Parnassus a half-century earlier. Moreover, the transformation of the campus could be measured in ways far more important than mere bricks and mortar. As the Moffitt Hospital and the medical sciences buildings took shape, physiologists (Leslie Bennett, Ralph Kellogg, Francis Ganong), biochemists (Harold Tarver, David Greenberg), and anatomists (William Reinhardt, Miriam Simpson, Ian Monie) made plans to create new basic science departments.The University itself was undergoing a huge metamorphosis in the postwar years as enrollment skyrocketed and new campuses were added rapidly to meet the demand. In 1958 Berkeley's first Chancellor, Dr. Clark Kerr, was appointed President of the University of California. Presiding over the design and implementation of the University Master Plan, Kerr became vitally involved in the fate of the medical school much as his predecessors, Daniel Coit Gilman, Benjamin Ide Wheeler, David P. Barrows, William W. Campbell and R. G. Sproul, had been. Kerr recognized that the postwar world of higher education was a new environment of research opportunities made possible by unprecedented sources of extramural funding. He also understood the political importance of expert service to the public to be provided by a state university. Throughout its history, the University of California's support of agriculture had been its most important contribution to the well-being of the state. As late as 1948, 38 percent of the university budget was invested in agricultural activities compared to 9 percent for medicine. From his vantage point as university president, Clark Kerr observed that health sciences could now be "higher education's best current ambassador," and he turned his attention to the development of science-based medical education for the University of California.

Also in 1958, in an unrelated move that had huge implications for San Francisco's clinical teaching environment, officials at Stanford University in Palo Alto moved their Medical School's clinical training to be closer to basic science instruction at Stanford. This move was highly contested by eminent Stanford clinicians who wished to stay in the more abundant clinical environment of San Francisco. Stanford's departure for Palo Alto created unequaled opportunities for UC professors, house staff, residents and medical students who took over the busy clinical services at San Francisco General, much to the advantage of the University of California.

By the mid-1950s federal grants from the National Institutes of Health soared to new levels bringing in unprecedented amounts of support to equip new research labs, hire research faculty and train graduate scientists. Pharmacologist Julius Comroe lost no time in recruiting investigators and applying for NIH training and research grants. The CVRI opened in 1958 and its first research programs involved participation of investigators from thirteen existing departments as well as CVRI staff. In an optimistic reaffirmation of Flexner's view of the proper configuration for a medical school, Comroe wrote: "Everything had suddenly come together in San Francisco. For the first time in fifty years, there was a structurally complete medical school with basic scientists and clinical faculty (a complete faculty) using the same corridors, lecture rooms, elevators, and lunchroom. Where once had stood an unimpressive group of outdated buildings housing only half the school's faculty, there was now a magnificent, connected group of high-rise buildings with new laboratories, many not yet occupied."Despite these high hopes for the benefits of reconsolidating the medical school, one skeptical onlooker, physiologist Leslie Bennett, observed that "proximity doesn't guarantee that you'll have collaboration." Indeed, despite the promise of new facilities, the Parnassus campus was dominated by clinicians with an entrenched system of financial arrangements who were a long way from a strict full time system. Although the arrival of the first-year basic sciences was heralded as a major improvement for campus instruction, this handful of new professors had little political clout on their new campus and would continue to be a minority voice in the medical politics of the Parnassus campus. In its first year, the CVRI was already fostering some important interdisciplinary research, but most influential campus department chairs had held office for many years with no outside review and remained suspicious of any radical campus change.

In 1958 the UC School of Medicine had a strong reputation for being a good regional medical school, known for excellence in technical surgery and expert physical diagnosis, but only a handful of new recruits were struggling to set up research programs. The most important question for the immediate future was how quickly this relatively isolated, tradition-bound west coast medical school would be able to integrate itself into the transforming mainstream of American medical education and biological research.

Millberry Union and the Social Unification of the Campus

Dentistry continued under the leadership of Dean Willard Fleming, whose popularity with students was well-known and whose stature as vice-Provost kept dentistry in the mainstream of the developing Parnassus campus. It was a fitting tribute to the School of Dentistry, and its longtime dean Guy S. Millberry, when, in 1958, the 175,000 square foot Millberry Union opened, for the first time creating, ample facilities for recreation, student housing, cafeteria, and a bookstore on the Parnassus campus. Millberry Union’s very existence was the direct result of Dentistry’s long history of promoting student body spirit, recreation and unity. The Millberry Union site on the north side of Parnassus Avenue had been acquired by the College of Dentistry in the early twentieth century and donated to the Regents for erection of a student union. Moreover, Dentistry’s maintenance of tennis courts on campus, its sponsorship of “the shack” cafeteria in 1921, and the Dental Supply Store in 1925, created a precedent for recreational facilities and served as a financial foundation for the 1958 facility. Proceeds from the cafeteria and store acted as a focus for matching alumni donations and state funds to build a state of the art student union.

Throughout the first half of the twentieth century, a disparate group of affiliated colleges and a training school for nurses had united geographically at Parnassus, and became mutually involved in delivery of patient care to the San Francisco and California public. Integration of the schools was a gradual process and was enhanced during the Depression by construction of the Clinics Building in 1933. Following World War II, they were nominally linked in the Regent’s formal naming of the University of California Medical Center in 1949, and by 1956, all four were designated as “Schools.” The construction of the impressive high-rise medical buildings along Parnassus Avenue, and the return of the Medical School’s basic science departments in 1958 was the final culmination of a long process. A campus observer in the mid-1960s, wrote that with the completion of Moffitt Hospital, two phases of the Medical Science buildings, and Millberry Union, “the interaction of the four schools became a reality in practice as well as theory.”Each school had, in its own way, heeded the call to professionalize by working for legal regulation, determining more rigorous educational standards, and absorbing and applying new scientific disciplines and technological developments. The University of California Medical Center and its fully integrated professional schools would now move beyond the instructional and professionalizing tasks of the early twentieth century into the era of federally funded research and ever more sophisticated modes of patient care. For the remaining decades of the twentieth century, the major institutional challenge would be to achieve an effective balance of teaching, scientific research, and patient care within a fully independent UC Health Sciences campus.

>> 1959–1989: Modernization and the Expansion of Scientific and Clinical Training